ACROPOLIS MUSEUM, First Floor Rampin Rider And Moscophoros

Language: English / USA

Language: English / USA

In this appealing open space, also dedicated to sculptures from the Archaic Period, I’m just going to point out two sculptures: the Rampin Rider and the Moscophoros.

The “Rampin Rider” is one of the most famous statues in the Museum because it is the only existing example of an equestrian statue from the Greek Archaic Period, dating to 550 BC. It depicts a young man on horseback, completely nude, with his face lit up by a smile. It is thought he may have been the winner of a horse race, because he is wearing a wreath of celery that was the mark of victory in such events. If you look carefully, you’ll see that the statue still has traces of red and black paint.

Observe the contrast between the rigid, schematic appearance of the torso and the sophisticated execution of the hair and the beard framing the face, lit up by what is known as the “archaic smile”, one of the simpler ways to sculpt the mouth.

Now press pause and restart when you reach the Moscophoros, a statue of a young man with a calf on his shoulder.

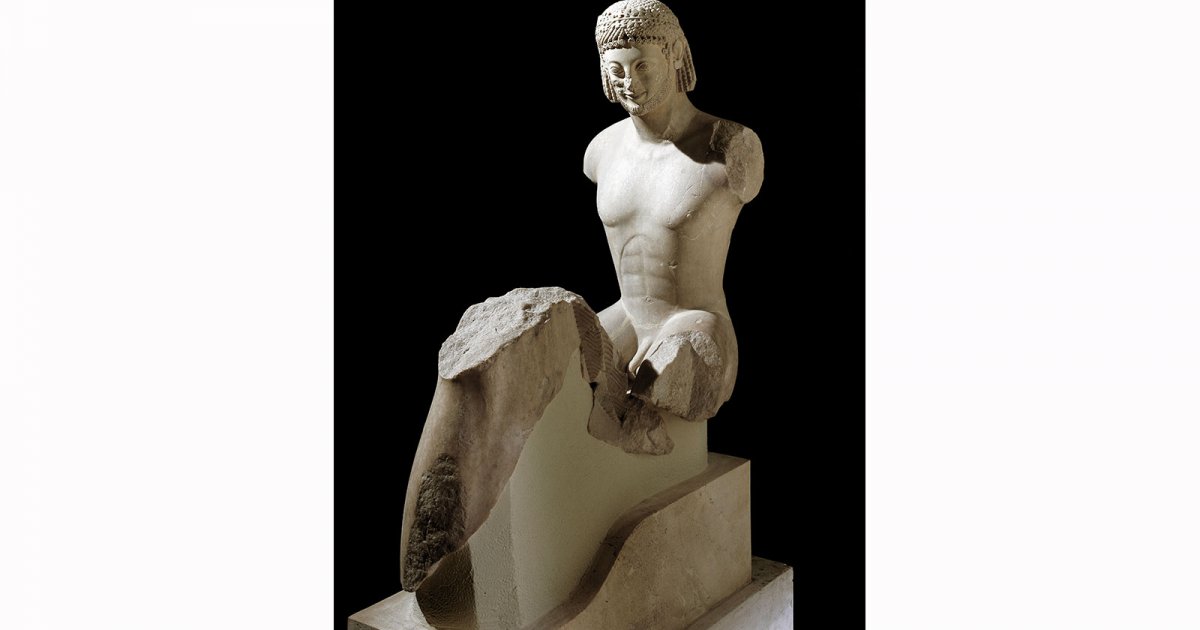

The “Moscophoros”, which means calf-bearer, portrays Rhombos, a rich, pious country gentleman, carrying a small calf on his shoulders to offer it as a sacrifice to the goddess Athena. At the foot of the statue is an inscription that reads "Dedicated to Rhombos, son of Palos".

The two figures blend smoothly with one another, thanks to how the contours are shaped, the way their heads are placed side by side and how the youth’s arms and the calf’s legs create an X-shaped composition. The wide-open eyes – which would once have been filled with glass paste, ivory and bone to color and enliven them – and the archaic smile give the figure a profoundly human expression. Like all works from this period, the head is not a lifelike portrait, but the ideal image of a man pleased to offer a gift to the deity.

An interesting fact: the beautiful head of the Rampin Rider is a plaster cast. The real head was found in 1877 and purchased by the French diplomat Rampin (hence the name given to the statue), who donated it to the Louvre in Paris, where you can still see it today, together with a cast of the rider’s torso and the horse. The rest of the work, recovered later, remained in Athens.